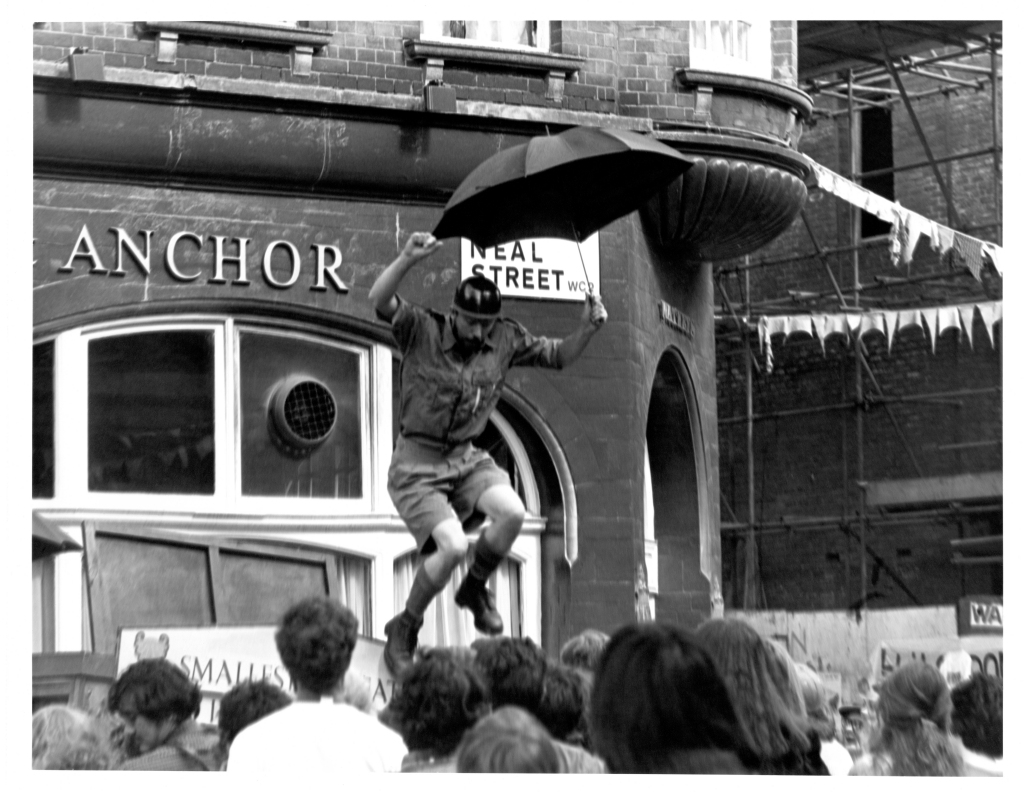

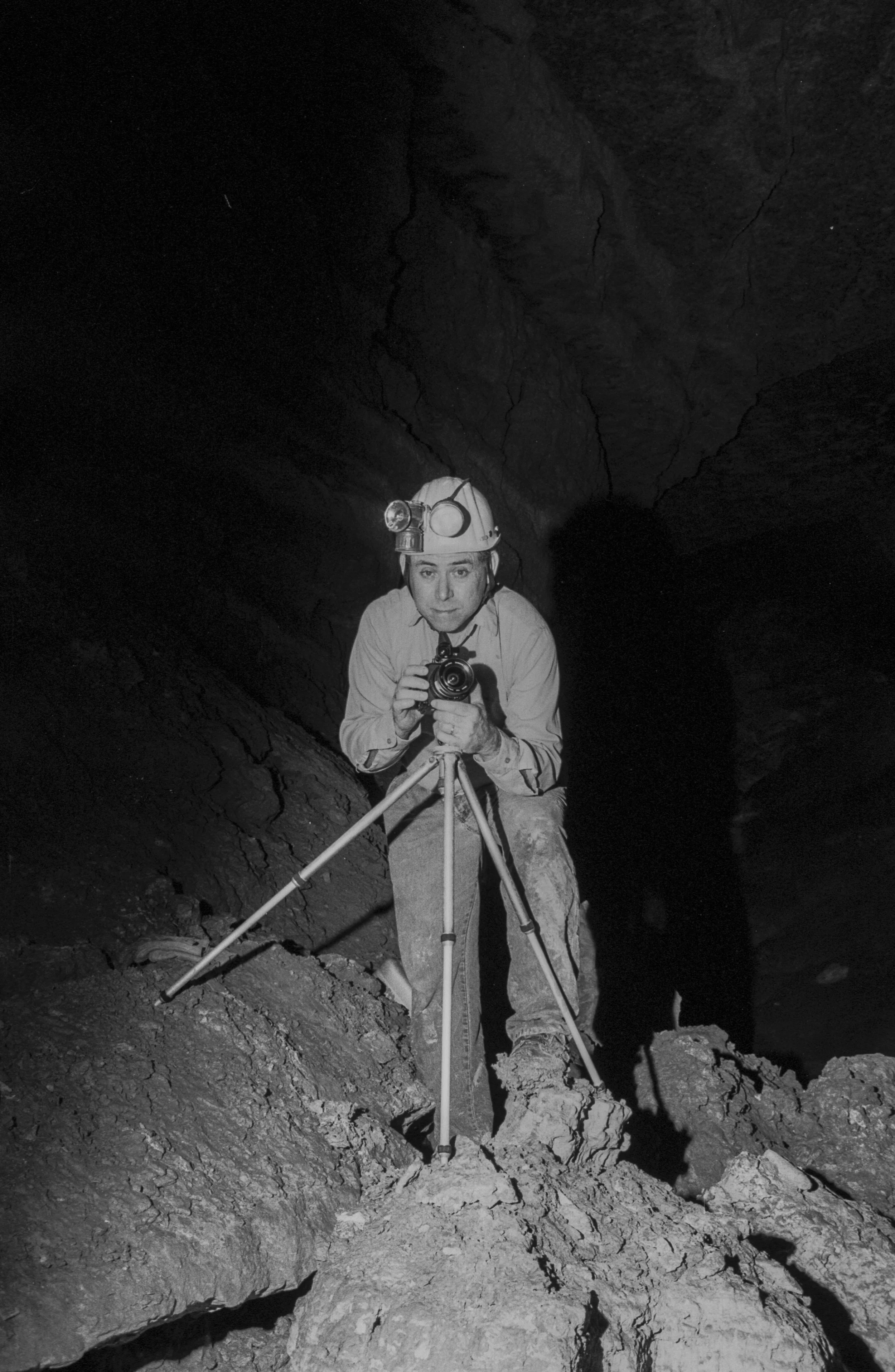

I have been taking photographs since the age ten using 120 format film cameras and then in my 20's got into 35mm film. As I now work my way through my fifth decade I am ever more aware of just how little I like the results of most digital photography, and am now trying more and more to bring the qualities of film to my photography.

Born in London, England in the same part of town as Don McCullin the photographer who is famous for having his Nikon F take a bullet from an AK47 and save his life in the Vietnam war, I now call North Texas my home.

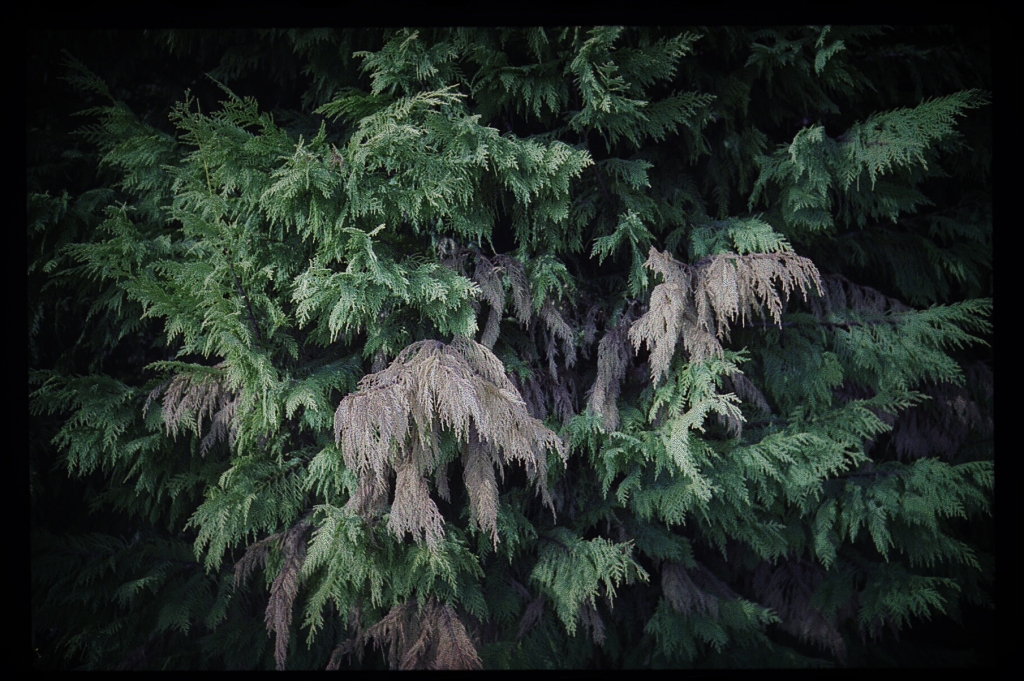

My approach is both deliberate and opportunistic. Slow and considered as well as fast and in the moment. This complete contrast results in images that span many genres and styles: I never know when or what might happen next, it's why I always have a camera with me and why this art never ceases to amaze and astound me.

I am currently TRYING to make a web site but it keeps changing and evolving, so I have no idea what new things will be there from one week to the next.

See more from film photographer Brian Richman at his website.

Read more from Brian Richman below

Featured Artist Brian Richman curates this week's Photostream.

In short, a nice and relatable conversation, a couple of very valuable opinions about film and an entertaining life story. I present you, our Featured Artist: Brian Richman.

I'm going to bust another scanning myth... That JPG files are rubbish!

If your file is going to be used in a low resolution use (like clip art, Facebook, more or less anywhere online in fact), then a JPG file is what you need. In some quarters this opinion is considered absolute heresy. "How dare you recommend that" and so on... But wait! There is a reason here... read on.

I'm starting out this installment by assuming you are new to film scanning. What's the biggest single problem you have? Apart from the terminology and technical juggling of options and places to click in the software, I bet its trying to get consistent and decent results. Well, here is a myth busted. Read on for the best place to start out.

The reality is that most film photographers today are neither 100% analog nor are they 100% digital but use some crazy mix of hybrid techniques to get their results. Sure there are those for whom the darkroom is the only place to print and there are those that will never in their entire lives set foot in one, but most of us are somewhere between those two extremes. Most of us who shoot with film, will therefore at some point in time also scan our prints and/or the negatives.

You may already have a scanner - I have gone through a collection of multi-function printer/fax/scanners in my time mostly for the printer, but have used just about all the Epson range at work. I can't afford the Epson that I'd like, so my own purchase is a compromise.

We seem to get a constant stream of questions about scanning in the Film Shooters Collective, very often resulting from a lack of familiarity with the terminology used or from the fact that someone has set a level of expectation very high but are not using software properly or in such a way that prevents them from meeting these high expectations. Fear not! Between us, we have some very experienced "scanners" who can lead you through the maze that seems to be set out with this subject.

I have just returned home from visiting an exhibition by English Landscape photographer Michael Kenna's of his "France" series. He has some very strong views and after comparing his work in real life with samples on a phone, I can tell you, I see what he means. For me, mobile images stink. In this short item, I say why I think this is the case. If you are serious about viewing images, don't do it on a phone screen. The only person you are fooling if you do, is you.

As this is the Film Shooters Collective (I assume we are all shooting at least some proportion of our photography using film), we probably scan the negatives and most likely print those scans using an inkjet printer so this almost certainly applies to us.

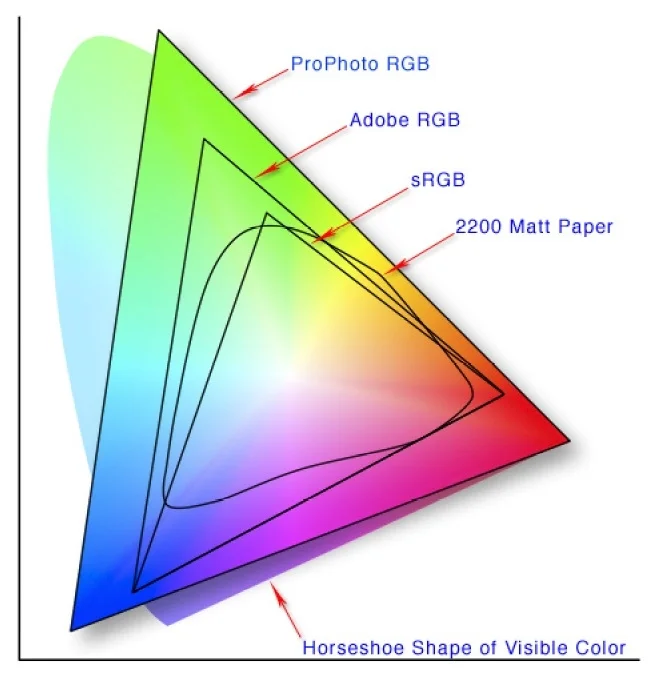

Back to basics: What is a "color space" and if there is more than one, which is better?

For most of us, whenever we touch a computer to process an image, however much it was produced using film (or glass or metal) as the support medium and processed in a chemical darkroom to deliver a negative or even positive “inter-image” as they were called, if the image as displayed or viewed in its final form is via some type of electronic medium (not media, medium – there is a huge difference) it becomes a hybrid.