Anyone who studies art knows that questions about the meanings of genres are nearly impossible to answer convincingly, or satisfyingly. To ask the question, “What is a portrait?”, is to invite disagreement. For one thing, portrait photography, as a genre, is almost as old as the photographic process itself; and if we consider the history of painting (and we probably should), the idea of making a portrait has existed for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. As a result, I’ve always found it important to maintain a relatively inclusive genre description of portraiture that is (despite its flexibility) still ‘distinct’ from other modes of photography, although not necessarily detached.

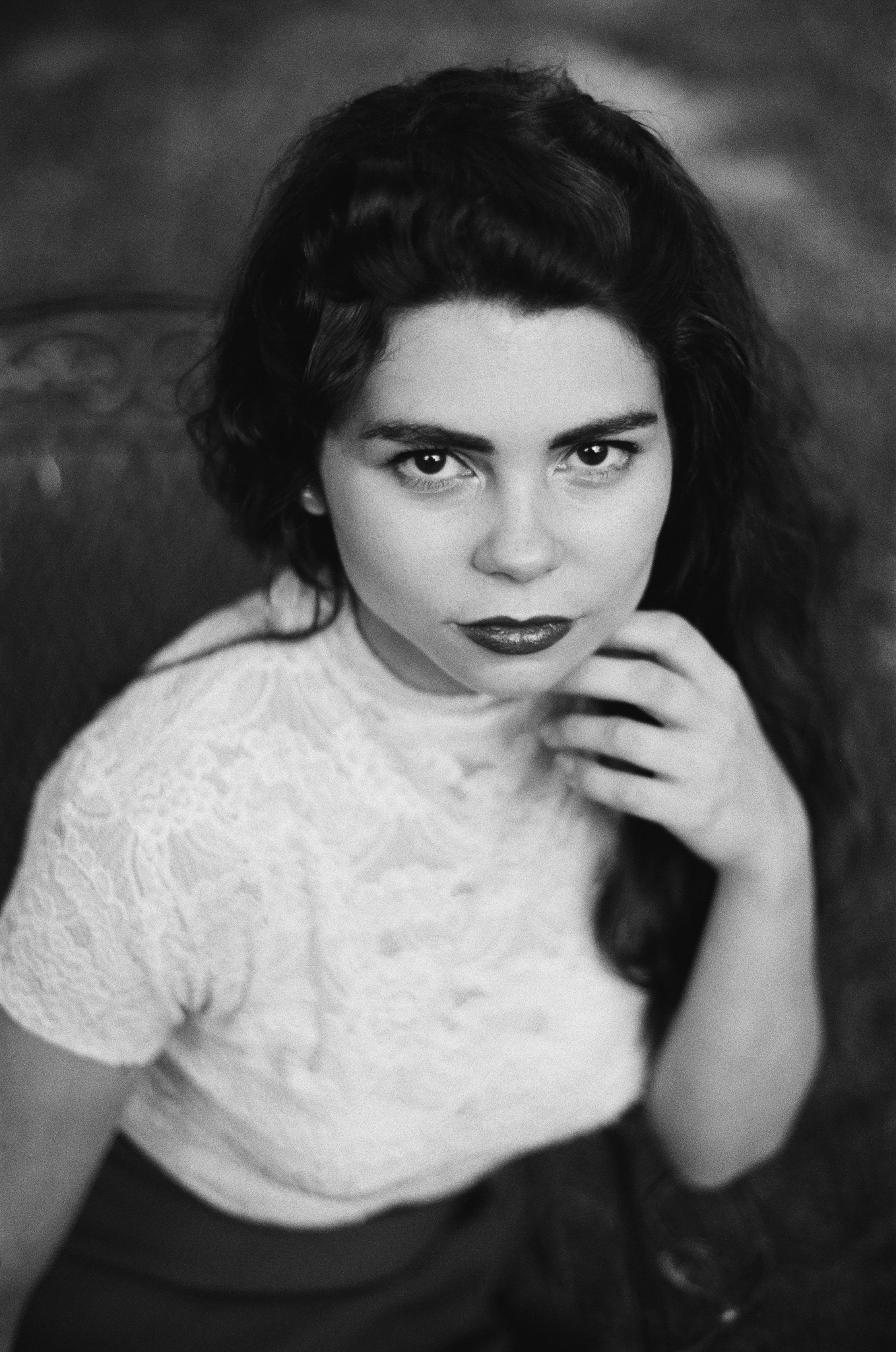

I consider myself a portrait photographer. For me the term has particular implications for the way that I approach my work. I have aesthetic and psychological intentions for an image. A portrait must have discrete qualities that mark its existence as somehow more profoundly personal than a purely descriptive image—or an image in the service of something other than the creative moment. There is an art to portraiture.

Irving Penn, arguably one of the most influential portrait photographers of all time, once remarked in an interview, “What I really try to do is photograph people at rest, in a state of serenity.” Penn was a master at recognizing and capturing moments of ‘rest.’ His 1945 portrait of Dorian Leigh and Maurice Tillet is a striking example. Tillet, a fearsome figure on his own, appears amused and unguarded as Leigh attempts to wrestle him into submission. The physical juxtaposition of the figures is contrasted by the seeming playfulness of Tillet’ s demeanor, in response to the aggressive Leigh. What Penn seizes upon is an honest moment between two public figures, as their personas slip behind and become lost in the unscrutinized ‘serenity’ of private play. Some amount of staging is likely to have occurred, but the moment is observably free from contrivance.

Internationally renowned French fashion and portrait photographer, Paolo Roversi, approaches the matter from a slightly different angle. In a recent interview, he speaks about his creative process in the studio:

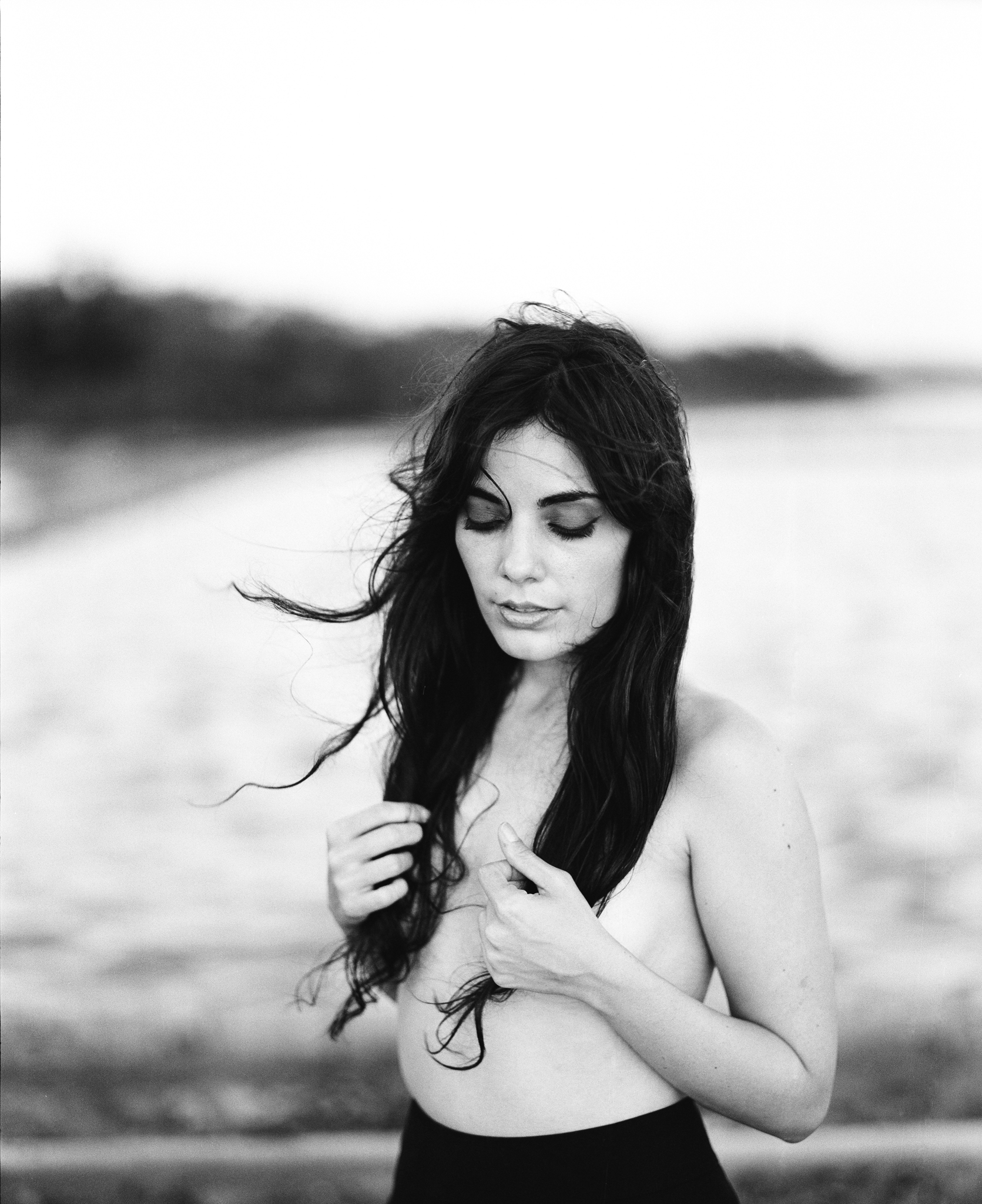

"My photography is more subtraction than addition. I always try to take off things. We all have a sort of mask of expression. You say goodbye, you smile, you are scared. I try to take all these masks away and little by little subtract until you have something pure left. A kind of abandon, a kind of absence. It looks like an absence, but in fact when there is this emptiness I think the interior beauty comes out."

The idea of subtraction is fundamental to Roversi’s work. As a fashion photographer, his images display a commitment to the reduction of visual elements to an essential minimum. Roversi is interested in the locus of abandonment, a period of voluntary surrender and vulnerability, when the subject’s unguarded humanity emerges from whatever dark corners in which it normally hides from view. Image-making is, for Roversi, a process of carefully peeling away layers of social pretense and aesthetic expectation, until the subject’s ‘interior beauty’ is exposed to the gaze of the camera. Within the contexts of the fashion industry, where visual emphasis is supposed to rest on externals (consumables), such an artistic intention is decidedly counter-intuitive, perhaps even radical. Even Roversi’s lighting techniques—widely imitated, but rarely employed successfully—seem less intent on illuminating exteriors (bodies, clothing, & environment) than they are on shining light on the hidden interiors of the subject. Paolo Roversi is, in short, a portrait artist, who found a niche for his creativity in the world of fashion: “I see and treat every image as a portrait, of a woman or a man or a boy– but the clothes are always there and they can make the interpretation of the image much more difficult.”

But we should not assume that everyone understands the act of image-taking assimply as Penn, or as romantically as Roversi. Writer and critic, Susan Sontag, asserted quite bluntly in the essay, “In Plato’s Cave” :

"there is something predatory in the act of taking a picture. To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed."

Sontag was, herself, photographed numerous times throughout her career, most famously by her partner, Annie Leibovitz. It is for this reason that I often wonder, when I re-read her words, if Sontag is recounting her personal experience before the camera, or if her statement exists broadly as an analysis of the photographic world in general, without regard for genre. When one views the many private and formal portraits that Leibovitz made of Sontag, there is very little there that would suggest either objectification or violation. But, of course, Sontag is likely referring to the privileged perspective that the artist has of her subject in that decisive moment of capture—a perspective that is hidden from the subject herself, and revealed only after-the-fact, in the form of the finalized artifact. Seemingly, the sitter is a passive participant in a kind of formalized examination.

While there is a great deal of truth to Sontag’s analysis, I believe that portraiture can make a claim to a more balanced distribution of power between sitter and photographer. Much depends on the methodology of the photographer and, of course, on her understanding of the genre within which she is working. Portraiture is assumed to be a more intimate genre. Unlike fashion photography, which always commodifies the appearance of an individual for the purpose of selling a product/lifestyle, in portraiture, the sitter herself is the primary interest of the photographer. Although it is perhaps still possible to claim that the sitter is ‘subject’ to an external agenda—that of the artist’s creative intention—the sitter is an active participant in the exchange. A portrait is a dance in which both participants have agreed to give and take.