The Genesis of The Dust

Written by: Simone Alterisio / Photos by: Matteo Prezioso

(Translated and adapted to English from Italian by: Matteo Prezioso)

What follows is an excerpt from the soon-to-be-published book

“La genesi della polvere” (The Genesis of The Dust,)

a testimony of what 53 years of civil war looks like.

The book tells of our trips in the Catatumbo, an impoverished, abandoned

Colombian region destroyed by both civil war and cocaine production.

At first it was only a blank page. It soon after moved onto an idea, a trip, and finally a book.

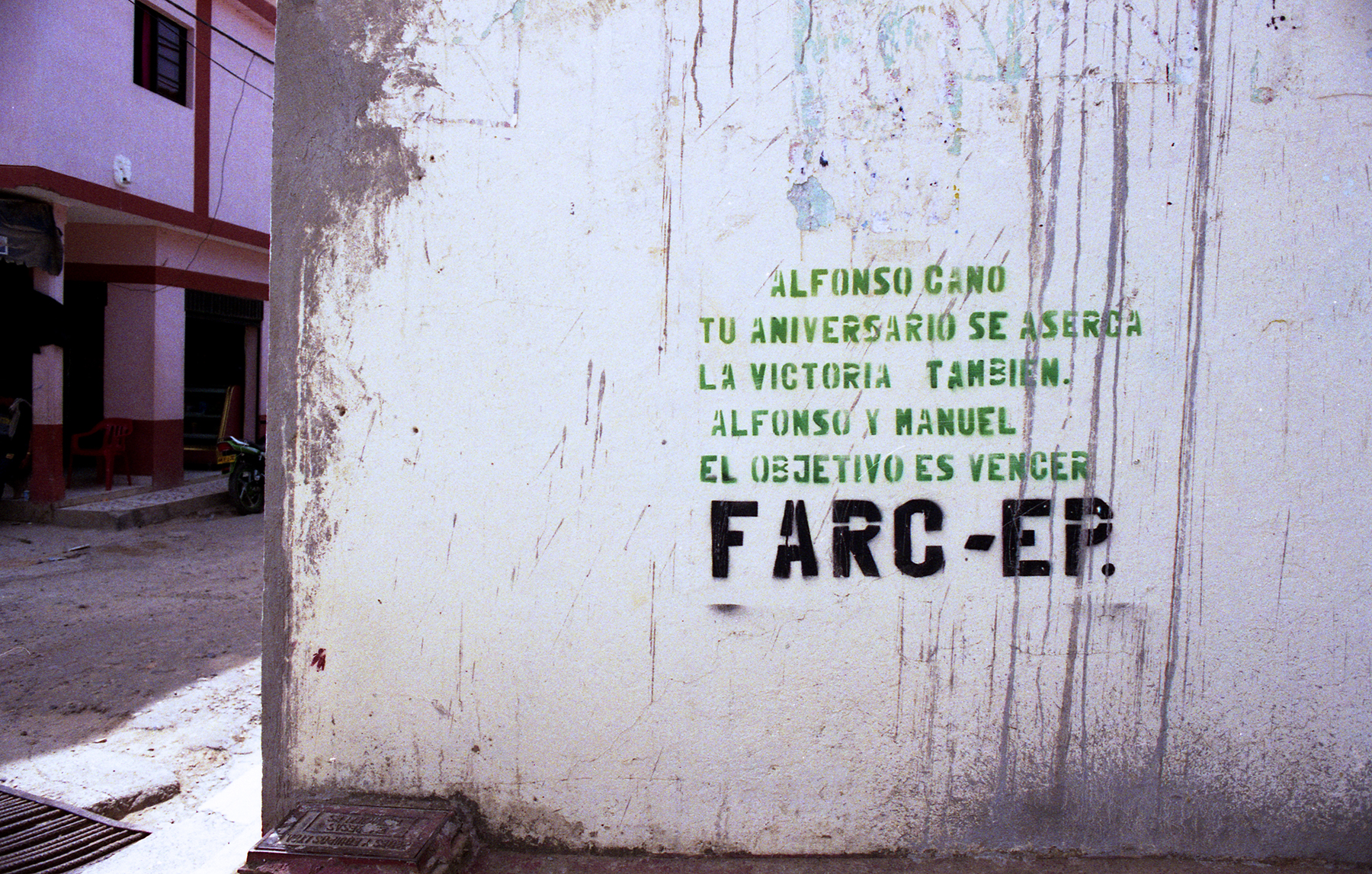

The subject? The Catatumbo, a region situated in the Colombian department of Norte of Santander, on the border with Venezuela. The reason? The whole area been torn apart from 53 years of civil war between the Colombian army, paramilitary groups, and a variety of leftish guerrilla groups.

The victims? As always, the defenseless. In this case poor, humble peasants who have constantly found themselves in the crossfire. But let’s return to the blank page for a moment; blank to most of the people once Catatumbo gets mentioned: word after word, line after line, photo after photo. No one knows what really is, and no one really wants to know what that is. So, we will fill all the blanks, and you – the reader – will accompany us on this journey. Our idea? A reportage, of and from this area, that will start from Colombia’s capital. To the chase, finally.

After our researches and investigations we left Bogotá. 14 relentless hours of bus and we reach Ocaña, the department capital. There we got greeted by Don Rito Alvarez, founder of the NGO “Fundación Oasis de Amor y Paz,” (“Oasis of Peace & Love” Foundation.) He was happy to guide us through this dangerous territory suffocated by this never-ending conflict, with the sole understanding to help him showing the outside world what is happening here. We then arrive to Abrego, a little city from where the NGO operates. A few days to acclimatize and we are on the road again.

Not even a full day of unpaved, bumpy roads on board of the NGO SUV (packed beyond imagination,) and everything gets green, a color that will become our companion.

Yes, everything is indeed green, a dominant color illuminating both mountains, and the blue sky. A few more hours of driving under the blows of a sun that burns our grilled skins and here it is, the reason for all that green: coca leaves everywhere!

Now, imagine a boy. Standing in front of the sea, he dreams of crossing it, even perhaps defeating it by swimming in order to reach the dreamed island. Victorious and happy, where everyone else could see madness, he would still believe in his dream.

Imagine him again, this time facing a mountain. He looks small, tiny, at the feet of a giant mountain, impossible to climb, such an unattainable mirage. But he keeps on dreaming, and in his head he is already on top hoisting the flag. He can finally talk to the sky, and maybe even quarrel a bit with it.

This time the boy is with his father at the stadium. Goal!!! The crowd screams and shakes in feverish excitement; eleven heroes, so invincibly beautiful, almost a myth. And the boy dreams; he is now the striker who runs and scores. Idolized by the crowd, only by nodding he would transform them as he pleases.

Imagine now that they could all be your dreams, those of your children and those of your grandchildren. They would no doubts motivate your life, enough to make you wake up to another day.

And just when you are imaging all this, a clean razor cut will make you forget it. For here, in this land, there is no place for that boy, and his dreams.

In this land, the only space left is for either being a “raspachin” (coca leaves picker,) or for joining the “guerrilla.” Both options have a common goal: you will never know what dreams are made of, as dreaming is out of the question.

In our journey we came across endless farmland, exclusively dedicated to the cultivation of coca plants; local youths are the perfect cheap labor, working as “raspachines.” The little money earned will be immediately browsed in alcohol and prostitutes, no matter the age.

The plantations are totally controlled by drug traffickers and the guerrilla (in this area there are 3 main Colombian guerrilla groups: the FARC-EP, ELN, and EPL.) These groups control the region through a dense network formed by their militiamen. And every peasant family is perfectly nestled in this lawless system.

Yes lawless, as the "legitimate" state is completely absent. Here the revolutionary groups deal with every aspect of daily life, with the coca business establishing all the rules that everyone must respect: coca will worry about road maintenance; coca will resolve conflicts between people; coca will pay for short moments of happiness.

In case it was not clear already, I will say that once more: the only product in this territory is coca. It allows a quick gain and demand is constant. Unlike agricultural products such as yucca or corn, coca does not require infrastructure such as roads, as it is moved around along mysterious and masterfully articulated paths inside the forest. Roads are for cars as forest is for coca.

Ironically, the peasants have to buy exclusively from the guerrilla the chemicals necessary for the coca-to-coke process; the same goes with all of the agricultural commodities needed by their families in order to survive. Products such as rice, plantains, yucca, beans, were once produced by themselves for both consumption and selling. Now they have became an asset of almost inaccessible wealth for their standard of living (although it must be said that recently, due to leavening price, the guerrilla requires landowners to produce just for themselves such alimentary assets.)

It is in this vicious economic cycle that, once again, we find the above-mentioned “raspachines,” one of the main reasons for our trip. As I said already, the money they quickly earn just as quickly disappears. There is no life planning, nor any prospect for a future life. Education is an unknown concept, as all they are taught is the “living here and now.”

This “economic model” both promises and delivers easy. One week goes, another one arrives, each time the same story: the coming week always start with no money. That means that a raspachin will easily work up to 14, 16 hours a day just to finish all that money on a weekend in just a few hours. By travelling there all we could see were mountains full of people, all of them collecting coca leaves on gigantic bags. Day after day we would get the same image, as they would get the shallow promise of two days spent at an ephemeral amusement park. Their work would break their backs, and burn their skins; kids with powder in their hands, and bombs in their eyes.

In our journey through those oceans made of green leaves, hidden in the jungle we finally found the “cambuches:” coke laboratories, all family-managed, fully dedicated to cocaine production. They represent the real first logistical base of this market of death.

In one of our visits, the owner explains us the process to make cocaine dough, done using various chemical agents and gasoline, products discretely transported by mules in endless valleys, where streets are now just a distant memory.

Once the work of those chemicals is accomplished, they will be poured into surrounding groundwater. Which means polluting their own land.

Whom we find in those labs are the very same kids who were picking coca leaves earlier on, now resembling little alchemists’ apprentices, under the instruction of more experienced adults. They are now actively producing coca paste, a process they seem to have been assimilating rather well.

All of the gases and chemical fumes emitted during this process make the environment both unbearable and unlivable, at least for our virgin nostrils. Yet to these people this is the norm; their organs have to make it through, and they do just that by adapting to the situation, simply surviving for as long as they can.

And so, finally, the cocaine dough leaves the Catatumbo. No one will really miss it, but no one will really be able to live without either...

Special thanks to the Italo-Colombian NGO “Fundacion Oasis De Amor y Paz” and its founder, Don Rito Alvarez - thanks for all the logistics, cooperation, support, and the wonderful friendship.

Note from the photographer:

Being the film nut I am, for those trips I could only go full analog, something I pretty much end up doing all the time. Choosing film over its digital counterpart has been a conscious decision, based on aesthetics and practicality.

Prior to the first trip, I was not sure what I would find, so I ended up selecting two cameras: a Nikon F4s with two AF-D lenses (50mm 1:1.8, and 24mm 1:2.8,) and a Rolleiflex Automat MX. Films used were a combination of Fuji & Kodak for color (Fuji C200, ProPlusII 100, and 200, and Kodak Gold 200, and Ultra 400.) For black and white I used Kodak & Ilford (Tri-X, T-Max, HP5+ & Delta 100.)

The second trip was way more demanding, but this time I had already familiarized with the area. I switched to the Olympus OM system. I made space for an OM-1, an OM-2n, and an OM-4ti, and an array of Zuiko lenses (24mm 1:2.8, 35mm 1:2.8, 50mm 1:1.4, 100mm 1:2.8, and the 135mm 1:3.5.)

The pictures shown here are only some of the color ones.

All photos protected by international copyright: @ 2014-2015 Matteo Prezioso

Connect

Film photographer Matteo Prezioso is based in Bogotá, Columbia . See more of his work on his Tumblr .