PICOS DE EUROPA [ASTURIAS]. EXPOSED FROM 4 AUGUST 2013 TO 8 FEBRUARY 2014

I discovered pinhole photography by chance. In 2007, during the "International Year of Science" I received a number of emails about workshops in Spain, and one of them included a DIY pinhole camera cutout model. I did not get around building one at that point, but a seed was firmly planted in my brain and two years later I discovered the Worldwide Pinhole Photography Day. The activities included a couple of workshops, to be held in a Community Civic Center of Barcelona. The pinhole workshop was sold out, so I ended up in a solargraphy workshop, in which I discovered a different way of doing pinhole long exposure shots. I was hooked!

Everything since then has changed my way of looking at photography. Pinhole photography makes you think before making a picture and study the peculiarities of each camera before getting used to it. That's the most rewarding way of making photographs. My main body of work lies in the field of film photography (lens and pinhole) and a sizable portion of my photographic practice is devoted to solargraphy, a specialized form of lensless photography that records the sun as it moves in continually shifting arches across the sky, resulting in thrilling images and new insights about the world around us.

RIU DEL INFIERNU VALLEY [PILOÑA, ASTURIAS]. EXPOSED FROM 16 JUNE 2013 TO 11 FEBRUARY 2014

Solargraphy was born in November 2000 when Pawel Kula, Slawomir Decyk y Diego López Calvín started the Solaris Project “involving the participation of artists, photographers and all other individuals interested in the photography, pinhole cameras and the movement of astral bodies. The project was conceived as to allow the participation of anyone interested no matter how far he/she is from the original creators of the project.” [check Diego’s website www.solarigrafia.com]

Solargraphy is a specialized form of long exposure pinhole photography that registers the sun trails as a consequence of its apparent movement related to the earth (known as “ecliptic”). The image is created using home made pinhole cameras (usually tin cans, 35 mm film canisters, PVC pipe, etc.) charged with photosensitive paper and fixed to some point for a period of time.

VILASSAR DE DALT [BARCELONA]. EXPOSED FROM 22 JUNE 2014 TO 18 JANUARY 2015

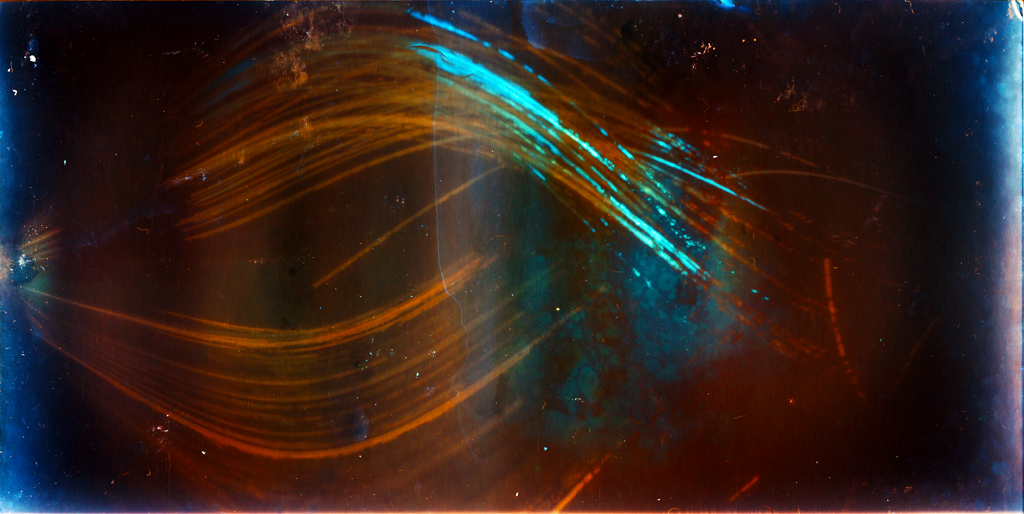

It consists in applying long exposure times, from one or more days up to months or even years. Over these so long exposures the photosensitive material placed inside the camera registers changes in the tonality of the emulsion as the light strikes it, both directly from the Sun or by reflection from other elements. Initially white or yellowish depending on the paper used, it gives rise to an observable image without the need of any chemical treatment (development and/or fixing). The image looks like a geometrically inverted (that is, upside down and left to right) negative presenting different brown, ochre or red tonalities only visible under a red or faint light to avoid it gets foggy.

TOUCHED BY THE SUN. [NEXUS II BUILDING. BARCELONA]. EXPOSED FROM 4 NOVEMBER 2014 TO 21 DECEMBER 2014

You may use any kind of photographic paper, both color or black&white paper; I only use black&white and these are my most liked ones:Ilford MGIV RC DELUXE Pearl [MG4RC44M], Ilford Ilfospeed RC DELUXE 3 [ISRC344M] and some Foma FOMATONE MG Classic warm tone. The differences in the paper are reflected in different coloring, contrast or tone but that is something open to investigation by the photographer. Other variables that can “affect” the end results are the metereological conditions, humidity, temperature . . .

HYPERSPACE!. EXPOSED FROM 4 AUGUST 2013 TO 7 SEPTEMBER 2014

The hardest thing is to frame, as much as the experience will help to get an idea of what can be in front of the camera. Normally you place the cameras pointing south, to better catch the Sun trails, but you can also play with the reflections in buildings, for example.

BORIZU BEACH [ASTURIAS]. EXPOSED FROM 6 APRIL 2014 TO 10 OCTOBER 2014 [WITH THE HELP OF DELFIN HEREDIA]

Once the exposure is done and the cans are collected I use to open them in a room with dim light to scan the image. You don’t need to develop nor fix the image, simply digitize it with a scanner to obtain a digital file and process it as you would do with any other photography. The idea is that the scanner makes a single pass over the image without stopping to avoid lines due to the scanner light. This is related to the computer memory, the software and the resolution of the scan.

PHOTOGRAPH BY: IKER MORÁN. THIS IS THE RAW IMAGE OF THE SOLARGRAPH SHOWN BELOW

PLAÇA DEL DR PERE FRANQUESA [BCN]. EXPOSED FROM 7 JULY 2014 TO 26 FEBRUARY 2015

For me, the most interesting part of this process is that, when removing the paper from the can with a subdued light, the image is already observed. I imagine that, when the photons strike the emulsion, in addition to the silver cations whose electrons are excited thus jumping to higher energy levels and yielding some silver complex salts. On the other hand, the gelatin, which is a partially denatured protein, that is, an organic chemical compound containing some mineral salts and water may also have some effect.

SCULPTURES IN PROCESS [GRANYENA DE LES GARRIGUES, LLEIDA]. EXPOSED FROM 29 SEPTEMBER 2013 TO A NOT DETERMINED DATE. THE CAN WAS ORIENTED TO THE NORTH AND NO SUN TRAILS WERE REGISTERED.

Another important feature of the picture is that it has a brown, ocher, reddish hues. . . ie have color (not black as elemental silver) and the quick scan (in RGB mode) and invert the negative to positive, the colors of the solar traces and the surrounding areas are observed. Can you imagine the feeling of seeing a photo on black&white photographic paper and get a color image? It is spectacular!

LIBRARY WINDOWS [INSIDE CAN MANYER LIBRARY, VILASSAR DE DALT]. EXPOSED FROM 14 JUNE 2014 TO 25 NOVEMBER 2014.

So, if you chemically develop the image as any copy in the photographic lab, you will get a complete black sheet of paper unless you use a very diluted developer. In this case you lose the color information and, at least for me, it has no sense. Another possibility is to fix the image, also with diluted fixer, but in this case you lose some information as you are eliminating a part of the silver salts present in the gelatin. Remember that the fixer removes all the remaining silver cations present in the gelatin after the developer has reduced (transformed) the excited silver cations (those that were stricken by some light photons) to metallic silver (elemental black silver).

SKYLINE [VILASSAR DE DALT]. EXPOSED FROM 24 SEPTEMBER 2014 TO 18 JANUARY 2015.

A recurrent question some people ask me is how many cameras do I have and how do I know where they are and when did I plant them. As you imagine, considering the exposure times needed to make a solargraph, a way to make a certain number of them is to plant lot of cameras wherever you go hoping to come back or asking some friend to collect them for you. So an Excel file allows me to keep track of the cans scattered around my house and those of my friends, some roofs and even the mountain. I can have more than 30 cameras active at once, although it is true that some are lost, disappear or simply doesn't show what was expected.

MULTIVERSE [INSIDE CAN MANYER LIBRARY, VILASSAR DE DALT]. EXPOSED FROM 14 JUNE 2014 TO 25 NOVEMBER 2014. THE CAMERA FELL OFF ITS ORIGINAL LOCATION PRODUCING THIS “HAPPY ACCIDENT” MULTIPLE EXPOSURE.

The last solargraph that I show you here is one that I already shared with you on Amy Jasek’s curated photostream of November 9th 2015 in the FSC web site entitled “de Revolutionibus”. It is a tribute to Nicolaus Copernicus and it was included in a text I wrote for a collaborative blog some time ago.

DE REVOLUTIONIBUS [CENTENNIAL OAK TREE IN AYARDES, ASTURIAS]. EXPOSED FROM 15 AUGUST 2013 TO 7 FEBRUARY 2014

Connect

Film photographer Jesús Joglar is also a scientist! Connect with him on his blog.

![PICOS DE EUROPA [ASTURIAS]. EXPOSED FROM 4 AUGUST 2013 TO 8 FEBRUARY 2014](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/50f89597e4b0df5f0985004b/1459273101019-431DBENPQ6P50KV3GVB8/image-asset.jpeg)

![RIU DEL INFIERNU VALLEY [PILOÑA, ASTURIAS]. EXPOSED FROM 16 JUNE 2013 TO 11 FEBRUARY 2014](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/50f89597e4b0df5f0985004b/1459273145116-SOF1RK54EM03WLTPS93X/image-asset.jpeg)

![VILASSAR DE DALT [BARCELONA]. EXPOSED FROM 22 JUNE 2014 TO 18 JANUARY 2015](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/50f89597e4b0df5f0985004b/1459273230343-1OR9NZLV6UTXRN8B8K13/image-asset.jpeg)

![TOUCHED BY THE SUN. [NEXUS II BUILDING. BARCELONA]. EXPOSED FROM 4 NOVEMBER 2014 TO 21 DECEMBER 2014](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/50f89597e4b0df5f0985004b/1459273644305-W13GBOBOBXYO52U90QN9/image-asset.jpeg)

![BORIZU BEACH [ASTURIAS]. EXPOSED FROM 6 APRIL 2014 TO 10 OCTOBER 2014 [WITH THE HELP OF DELFIN HEREDIA]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/50f89597e4b0df5f0985004b/1459274017164-XVQK38I0FFCJASNN332O/image-asset.jpeg)

![PLAÇA DEL DR PERE FRANQUESA [BCN]. EXPOSED FROM 7 JULY 2014 TO 26 FEBRUARY 2015](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/50f89597e4b0df5f0985004b/1459274260507-JFMN1EXOEE248NB4ZH6Y/image-asset.jpeg)

![SCULPTURES IN PROCESS [GRANYENA DE LES GARRIGUES, LLEIDA]. EXPOSED FROM 29 SEPTEMBER 2013 TO A NOT DETERMINED DATE. THE CAN WAS ORIENTED TO THE NORTH AND NO SUN TRAILS WERE REGISTERED.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/50f89597e4b0df5f0985004b/1459274360955-LWFPR2QSPK2ZYNWRX64R/image-asset.jpeg)

![LIBRARY WINDOWS [INSIDE CAN MANYER LIBRARY, VILASSAR DE DALT]. EXPOSED FROM 14 JUNE 2014 TO 25 NOVEMBER 2014.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/50f89597e4b0df5f0985004b/1459274436540-VZKVIUMVMNP72QOFIC1R/image-asset.jpeg)

![SKYLINE [VILASSAR DE DALT]. EXPOSED FROM 24 SEPTEMBER 2014 TO 18 JANUARY 2015.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/50f89597e4b0df5f0985004b/1459274519389-NSVAOKY6B6D0HZF7SR3M/image-asset.jpeg)

![MULTIVERSE [INSIDE CAN MANYER LIBRARY, VILASSAR DE DALT]. EXPOSED FROM 14 JUNE 2014 TO 25 NOVEMBER 2014. THE CAMERA FELL OFF ITS ORIGINAL LOCATION PRODUCING THIS “HAPPY ACCIDENT” MULTIPLE EXPOSURE.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/50f89597e4b0df5f0985004b/1459274652724-FGHO49I47WJ1F402H6E7/image-asset.jpeg)

![DE REVOLUTIONIBUS [CENTENNIAL OAK TREE IN AYARDES, ASTURIAS]. EXPOSED FROM 15 AUGUST 2013 TO 7 FEBRUARY 2014](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/50f89597e4b0df5f0985004b/1459274739548-FGIX4P1WPKX5Z5HD1IR3/image-asset.jpeg)