On August 21, 1968, 2,000 Soviet and Warsaw Pact tanks rolled into the Czechoslovakian city of Prague, accompanied by 200,000 troops. The ostensible goals of the invasion were to reassert Soviet dominance and to curtail reform legislation of the Prague Spring, a liberalization movement that swept the capital earlier in the year, under the leadership of Alexander Dubček, the First Secretary of the KSČ. The invasion ushered in a new phase of Stalinist rule, which would not be overturned until 1989, following the events of the famous Velvet Revolution.

One year after the invasion, Magnum Photos released a series of photos by an “unknown Czech photographer” for publication. The images were smuggled out of Europe at tremendous risk to the photographer, who, still living behind the Iron Curtain, would have been arrested, if identified. The photographer, known only as P.P. (Prague Photographer), was awarded the Overseas Press Club's Robert Capa Gold Medal award in 1969, but he would not be free to take credit for his images of the 1968 invasion for another sixteen years.

Thus began the photojournalistic career of Josef Koudelka. In 1970, he was granted an exit visa to visit England. Out of concern for his own safety, Koudelka would not return to Czechoslovakia until 1990. Over the next twenty years, he worked throughout Europe as a Magnum Photographer, publishing books, and exhibiting work. In the duration, existing mainly on money from grants and awards, Koudelka became one of the most celebrated documentary photographers of all time.

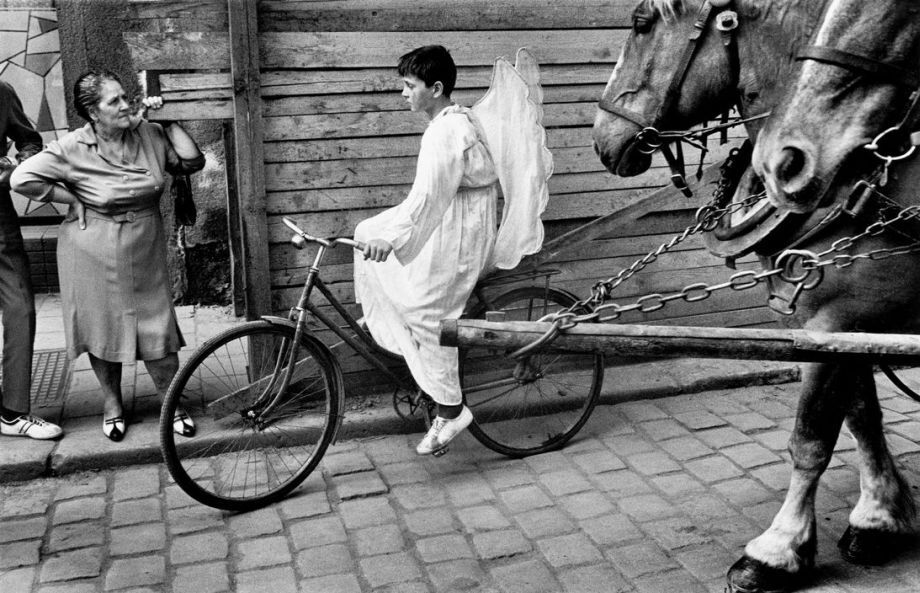

Koudelka published his most recognized book, Gypsies, in 1975. The images, taken before the Warsaw Pact invasion, emerge from years of traveling throughout Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Spain, and France, documenting Roma identity. In an interview for Le Monde, Koudelka describes this time photographing the Roma as a period of great difficulty, made possible only by a tenacious commitment to the work. “When I was photographing gypsies in Czechoslovakia, when I was living with them, sleeping outside, they would leave someone with me to make sure nothing happened to me. Afterwards, in exile, they felt that I was in a more difficult situation than they were. They told me, ‘It must be difficult for you to travel the world alone.’ And I remember one little English gypsy asking me, ‘When was the last time you saw your family?’ It was the way I had chosen to live my life, and they couldn’t understand it.”[1]

The portrayals are stark, yet poignantly empathetic. Koudelka’s choice to photograph the Roma using a wide-angle lens (25mm) creates a deeply intimate connection with his subjects. He often is up close with his camera, at times seemingly participating in the rituals of everyday life. Interiors are open to the viewer in a way that contextualizes the lives of the families being photographed.

Following the publication of Gypsies, Koudelka continued living in Great Britain as a political exile (“Nationality Doubtful”). As a photographer, he traveled throughout Europe, working independently, living in a way that seems inconceivable by contemporary standards. “For sixteen years I worked for no one. I never took a commission, never took pictures for money. I scraped by, trying not to have any possessions. I didn’t pay rent for 16 years. I didn’t want to have a home. I didn’t need much, just a sleeping bag, a pair of shoes, two pairs of socks, and one pair of pants per year. A jacket and two shirts would last me three years. I was able to live for several years off the money I earned from the Magnum sale of the photos of the invasion. Then there was the sale of the archive photos. And I was able to remain independent through various grants and prizes.”[2]

Koudelka’s next major book, aptly titled, Exiles, was published in 1988. The collection of photographs stands as a record of Koudelka’s solitary wanderings, “following annual folk festivals around Western Europe from early spring to late fall, then printing during the winter months.”[3] While many of the images are gloomy, menacing portrayals of life existing at the boundaries of acceptability, Koudelka demonstrates a tender curiosity about his subjects that is instantly reminiscent of Gypsies.

Exiles is both extensive in scope and unrelenting is its non-commercial posture. A disquieting restlessness bubbles under the surface of the work. An Odyssean project of this magnitude is perhaps achievable only by a photographer like Koudelka, who is neither fettered by the burdens of a homeland, nor pulled off course by the siren call of paying clients. Like Ulysses before him, Koudelka follows the meandering, unpredictable route that Fate offers, uncovering, in the process, indescribable wonders.

In recent years, Koudelka has turned his attention to panoramas. This work has taken him to Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Greece, Libya, Algeria, Turkey, and through out Europe. Josef Koudelka has worked as a Magnum photographer for over forty years now. He is recognized as one of the true masters of photographer, exhibiting work around the globe. One can find an extensive collection of his work on the official Magnum site.