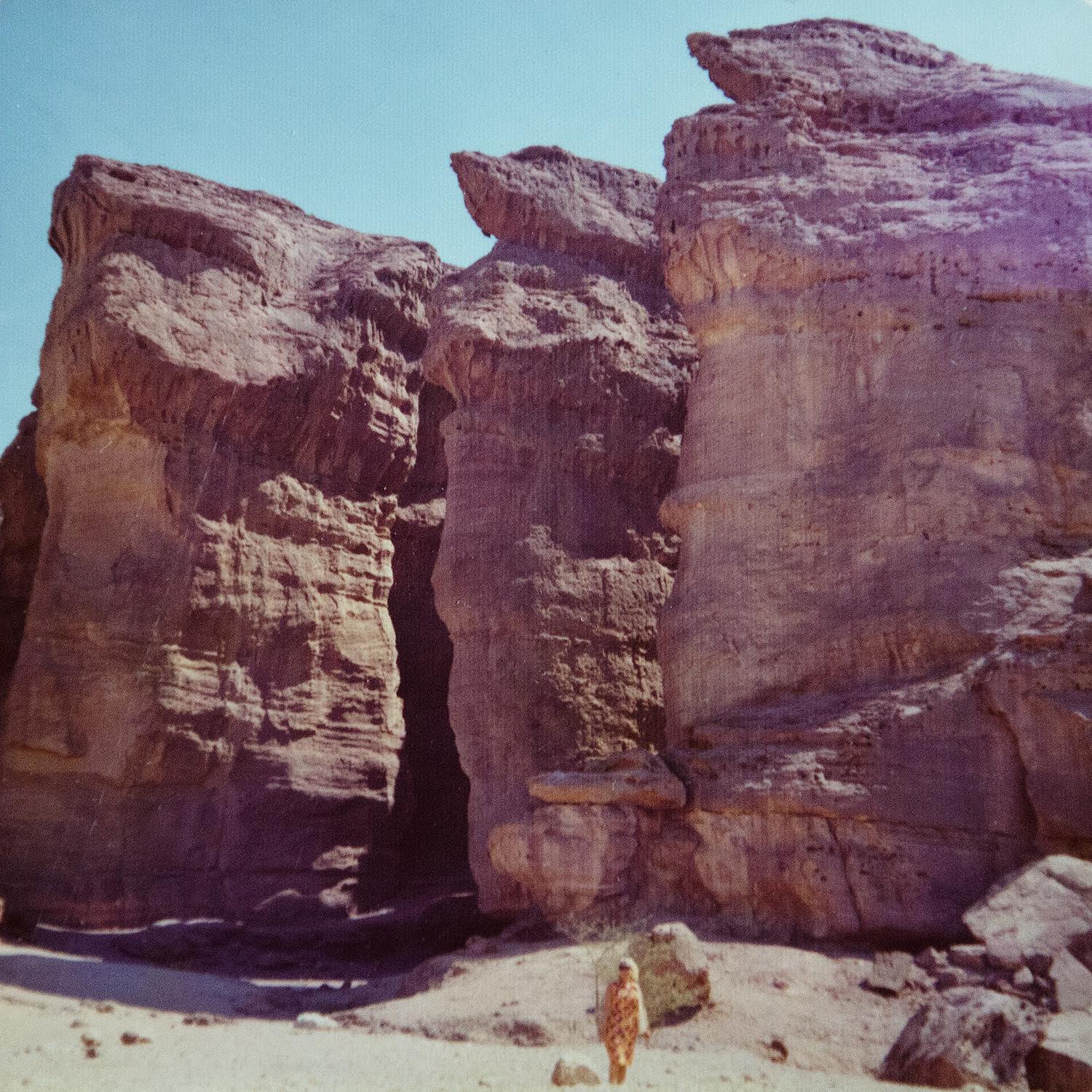

The year was, I think, 1975. I was in grade 8 and on a school photography club outing. I remember feeling somewhat embarrassed to be using my father's boxy 1950s TLR, a Ricoh Diacord L. In fact I remember another student, sporting an Olympus OM-1, called it a “shitbox”. Soon after that, I hauled the Diacord all through a family trip to Israel, I convinced my father to spring for a 35mm SLR and forgot about the Diacord for decades. We gave it to my nephew eventually.

One of the earliest images I made with a Diacord on a school photo club outing, circa 1975. Unknown black and white film. Scanned from a print.

Pillars of Solomon, Eilat Israel, 1975. Probably Kodacolor II film. Scanned from a print.

Fast forward to 2013, and I was, by then, a digital SLR veteran, earning some money with my digital equipment, but beginning to be interested in film again for my own fun. After going through a few 35mm film rangefinders and SLRs, I noted two things: First, 35mm film SLRs, at least the more modern plastic-bodied autofocus models, tended to handle so much like digital SLRs that the experience of using them was not satisfyingly different. Second, you need a really good scanner to pull enough detail out of a 35mm frame of film to approach a good digital image in some key image qualities.

I wanted to play in medium-format again, but this time purposefully and unapologetically. A Diacord L—the exact model I had used all those years ago—came up on the local buy and sell internet site in Ottawa, so I bought it for old time's sake. It immediately felt familiar in my hands, even the feeling of how the spring tension increases as you pull the shutter cocking lever to the right for the Seikosha shutter. The muscle memory had never been lost! Unfortunately, the camera was pretty dirty and had a sticky shutter. I attempted to take the lens elements apart to douse the shutter in lighter fluid and ended up getting some gearing misaligned so that the actual aperture didn't match the readout, and would not open beyond f5.6. I sold that Diacord, but even as my armory of other medium-format cameras increased, I wanted to have a Diacord again. A couple of years later, a suitable candidate came up on ebay, so I bought it, again the same model my Dad had bought around 1958.

A studio shot with off-camera flash, 2014. Ilford XP2

I think just about anyone who shoots medium-format should have at least one TLR. It is a different experience from just about any other type of camera. First, the frame is square. Even if you think that's just a convenience so you don't have to tilt the camera to shoot verticals, and that you will crop your frames later, I think you will find yourself composing to fill the square, making more square images, and liking it. Second, the experience of composing with both eyes open looking at a ground glass screen is unique. Everything seems more 3-dimensional. I like to just walk around looking at things through the viewfinder. Third, the mirror doesn't flip. You can see any blinks at the instant of pressing the shutter, and you can hand-hold the camera at relatively slow shutter speeds. The separate taking and viewing lenses also are nice when you are using filters, especially for infra-red photography, as they don't obscure your view.

Okay, let's say I've convinced you that TLRs are a good thing. Is the Diacord a good model to consider? Definitely yes. As TLRs go, there are essentially just a few features that differentiate one from another. Here's how the Diacord stacks up. First, consider the lens. The top tier in TLRs, the Rolleiflex models, have multi-element Planar or Xenotar lenses, which are known to be superb. The next tier down includes the Rolleicords, the Yashica-mats, Autocords and Diacords. These all feature 4-element tessar-formula lenses. I only have personal experience with the Autocord Rokkor 75mm lens and the Diacord Rikenon 80mm lens. I find both of these excellent. There is another tier in all these brands, generally from the mid 50s or earlier, which used 3-element lenses. In the Ricoh line, the 3-element lens models were called Riconars.

River Ice, 2017. Ilford Delta 400. Yellow filter. The Rikenon lens is plenty sharp for my needs.

River Ice 2017. Ilford Delta 400. The lens is remarkably free of ghosting for an old single-coated design. Here the sun was directly in the frame.

Second, consider the winding mechanism. While the Rolleiflexes, Yashica-mats and Autocords have crank winding mechanisms which also cock the shutter, the next tier, which in the Ricoh line included the Diacords, had knob wind with auto-stop at the next frame. You have to manually cock the shutter for each shot. I'm happy enough with that; in fact, I would be satisfied with a red window. Less to go wrong. I also find the pull-to-the-side cocking lever of the Seikosha shutter to be haptically satisfying for some reason. It's also handy for loosening up a sticky shutter with the lens cap on before taking the real shot. There are also Diacord models that had a Citizen shutter with a different cocking lever.

Third comes the focus ergonomics. Here I assert that the Diacord has the most wonderful focus control of any TLR. A unique see-saw, which Ricoh called the “Duo-lever” allows you to put your two thumbs on either side of the lens board and push down on one side or the other to adjust focus. Here's a little .gif to show you how it works.

The unique “teeter-totter” focus lever.

Next is metering. The Diacord L model had an uncoupled selenium meter. The cell is behind the nameplate on the front and has two ranges. When the nameplate covers the cell, two slits expose just a small fraction of the surface to light, so it reads in bright light. When the cover is flipped up, the whole cell is exposed, so it reads in dim light. Simple and smart! The meter needle is read from a window on a circular calculator on the right side of the camera. The meter reads out in LV units—common in the late 50s, which you manually transfer to shutter speed and aperture settings using the readout scales above the viewing lens. Everything is viewed by looking down from above. The meter in mine still works, although not so accurate in dim light. If you don't care about a built in meter, the Diacord G model lacks a meter, but be careful, as some earlier versions of the G have the simpler Riconar lens.

Finally, there are some features of TLRs that are usually not deal-breakers, but are worth considering. The Diacord has a hot shoe, which I think was rare in 1950s cameras. My model, which has the Seikosha MXL shutter, also has a self timer. The shutter button of the Diacord, as with Yashicas and the original Nikon F, is not drilled and tapped to accept a modern cable release. You have to obtain a “Leica nipple”, a little accessory that screws into threads which surround the shutter release sleeve, and then attach your cable release to that.

I've used my Diacord out in -20C weather and the shutter was still reasonably accurate. When I carry it on the street, it always attracts comments—no, not “is that a Rolleiflex?”, but more like “what is that”, “cool!”, “old school!”, “Is that a movie camera?”.

At the moment, the Ricohs are the sleepers of the TLR world. You can find a serviceable one on ebay for under $100 USD and then consider cleaning it up yourself, or sending it for a clean lube adjust if it's too grotty. Really, as long as the lens is not full of fungus and the shutter works at all, there's not much else to go wrong. I would recommend getting a lens hood, as the lens front element is only single coated and not deeply recessed. There are very inexpensive plastic lens hoods that use the Bay 1 filter mount; however, then you can't also mount a filter. For a bit more money you can get a metal lens hood that mounts over the outside of the Bay 1 bayonet and this allows you to also put filters on the inner bayonet.

Coming full circle, I've returned to my photographic roots.

Portrait of my father at 96, 2017. He bought our first Diacord circa 1958. Aperture about f5.6. Portra 160.

Connect

Film photographer Howard Sandler is based in Canada. See more of his work on Flickr.