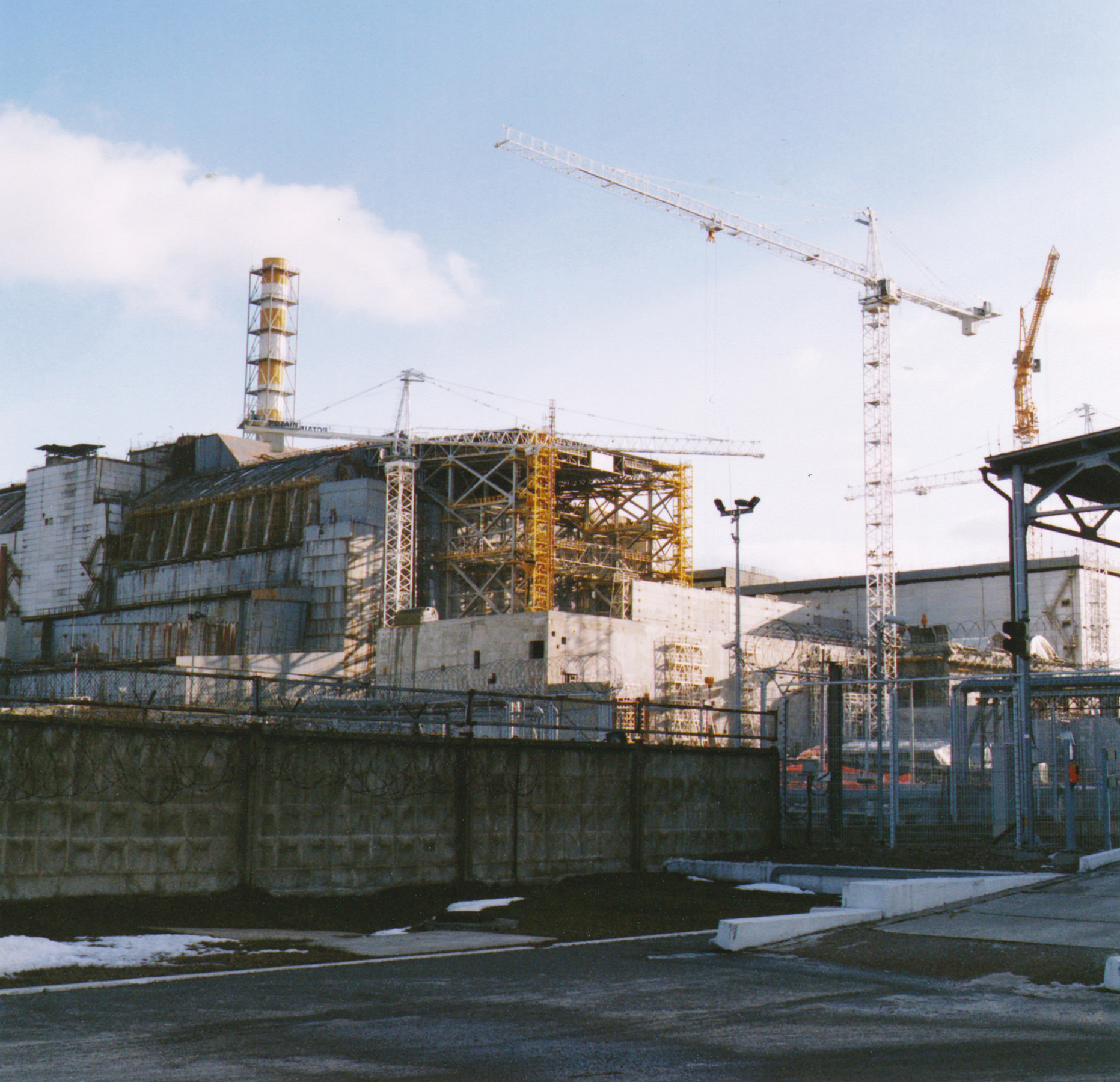

On Saturday 26th April 1986, Reactor 4 of the Chernobyl Power Plant went into meltdown and set in motion the worst nuclear accident in history. A systems test gone disastrously wrong triggered an explosion that unleashed a radioactive cloud that covered Western Europe.

The consequences were catastrophic. Thirty one members of staff were killed in the initial blast. Deaths due to radiation poisoning and related cancers are almost impossible to correlate but the lowest estimate starts at 4,000. Contamination of soil rendered surrounding areas uninhabitable for 20,000 years and led to the mass displacement of 350 000 people. Ultimately, the financial and psycho-social cost of the disaster precipitated the collapse of one of the world’s largest empires.

Nearly 30 years later, I am wandering through one of Chernobyl’s abandoned sport centres, staring down through the glass of my Hasselblad and trying not to fall into an empty swimming pool.

Despite the imposition of an exclusion zone covering a total of 819 square miles which is patrolled by armed guards, getting there isn’t too difficult. I wake early and meet my guide Serj in the Ukrainian capital of Kiev and we begin the 2 hour drive. I am shown how to work a Geiger counter and proceed to watch a weird mix of unsettling documentaries and awful rap-rock music videos where everyone is doing parkour through the ruins in hazmat suits. The day is cold and bright as we bounce down bumpy roads and avoid snow drifts. I learn that snow is good because it masks the radiation in the soil (but you still can’t use a tripod). We run through our day’s itinerary; a close-ish look at Reactor 4, the gigantic but secretive radar array and the abandoned city of Pripyat.

Pripyat was supposed to be a Socialist utopia, a ‘Nuclear City’ built for the 49,000 workers of the plant. Clean energy would provide full employment for the young (the average age was 25), modern city with a port, several schools, hospital and fairground. On the day of the 26th , the radiation from the accident exceeded background levels by a thousand times but the evacuation did not happen immediately. Residents went about their daily lives, with the apocalyptic smoke cloud rising from the reactor being explained away officially as ‘steam’. A day and a half later, the population were told via loudhailer that must gather identification papers, personal items and clothes enough for 3 days away whilst the military briefly dealt with an accident. They never went home again.

Walking through Pripyat’s empty streets and abandoned buildings is one of the more surreal experiences I’ve had. In the silence there is a powerful sense of emptiness and loss, like exploring a localised apocalypse. Trees grow through high school basketball courts, lacerated grand pianos block off staircases and there are gas masks everywhere. Whilst smashed out windows and graffiti mark out vandalism and decontamination work, you still get the impression that time stopped here in 1986.

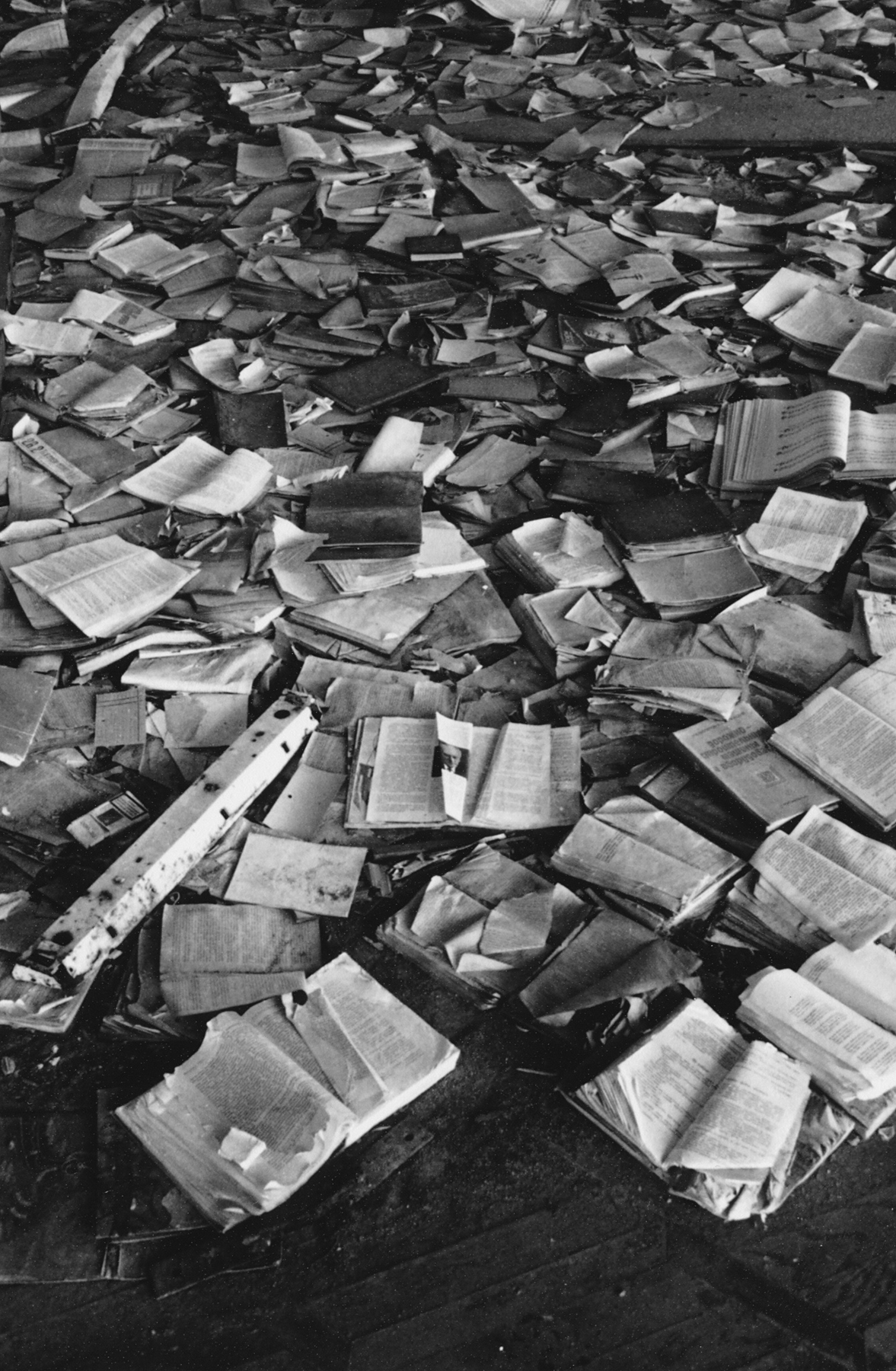

Akin to a modern day Pompeii (minus the spooky plaster casts), the city is full of artefacts from a society that no longer exists. One place this is especially evident is The Palace of Culture, a grand building where artistic and recreational activities took place surrounded and supported by the ideology of the USSR.

Behind the wrecked main stage of the theatre, the prop room is stacked with paintings of Lenin and other fathers of the Revolution that have seen the business end of an axe. I apprehensively tip-toe into the library where the floors are lined with open books. “It’s OK to tread on these books” yells Serj, scaring the hell out of me, “they’re all Stalinist propaganda!” Looking down I see a fox sharing the fruits of his labour with his forest friends. There is an ashen boot mark on it.

Despite the obvious desolation, the larger area of Chernobyl is not completely deserted of people or wildlife. A hundred people (mostly elderly) re-settled their old homes shortly after the accident, refusing to believe the state warnings. Having lived through the Nazi occupation and the man-made famines of The Holodomor, these people didn’t fear the invisible enemy of radiation. They are very much alive and making moonshine today.

Animals flourish within the exclusion zone, with the number of wolves, elk and wild boar being much higher before 1986. Without agriculture or hunting, it has become a de facto nature reserve and the Przewalski’s Horse, which was previously extinct in the wild, is now thriving. It is bizarre to think that human interaction is worse than a nuclear accident for the ecosystem.

There are also a large number of workers decommissioning the site, liquidating nuclear fuel and constructing a new $2 billion ‘sarcophagus’ to protect and cover Reactor 4 for good. There a few facilities for visitors and I finish the day by eating fish and chips at the Chernobyl Café.

In the dark bus back to Kiev, I consider the reality of living under a communist regime, how accurate the Call of Duty level is (very) and why my morbid curiosity draws me to such dark places.

I find the physicality and freedom of exploration to be profoundly exciting. Measuring the thin veneer of civilisation and making pictures of how things come apart is something that really resonates because, for me, the unpredictable is beautiful.

Photography, used as an anthropological tool, gives me a deeper understanding of my own place in history especially knowing exactly how a swift and terrible event could upend it all.

The bus door swings open. “Nice to meet you,” says Serj, “see you next time an apocalyptic industrial accident terrorises our country!”

Pictures taken with

Hasselblad 500 c/m, Portra 400

Lomo LC-A Wide, Portra 400

Contax T2, T-Max 400

My tour was conducted by SoloEast who come highly recommended.

Further Resources

A brief history of the disaster

Chernobyl and the fall of the Soviet Union

Disposable Citizens ( a photography project giving residents of the exclusion zone disposable

cameras)

Winter on Fire (an amazing doc about the 2014 revolution)

The Russian Woodpecker (doc about a Chernobyl survivor uncovering a dark secret)

Connect

Film photographer Richard P.J. Lambert is based in Birmingham, United Kingdom. Check out his work on our site, and connect with him on his blog and Instagram .